- Home

- Cleo Odzer

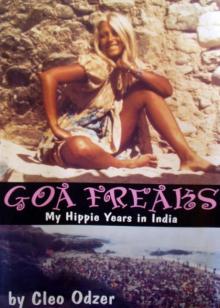

Goa Freaks: My Hippie Years in India

Goa Freaks: My Hippie Years in India Read online

v 1.0 Converting pdf. Джим, 23.10.2013

Goa Freaks

My Hippie Years in India

Acknowledgement

With special thanks to Richard Franken for his continuing friendship since these old Goa days and for his help and support with this book and with Patpong Sisters. I'd also like to acknowledge his photographic talent. Many of the photos used here are his.

July 1979

"BAKSHEESH," MUTTERED the beggar, thrusting his palm at me as I walked through the Colaba section of Bombay. He should have recognized me by now. In that rainy monsoon, could there have been more than one young foreign woman with blue eyes, blonde hair, and a diamond in her nose? He had not gotten a rupee from me yet, and I'd been down that street every day the past week. Glaring at him, I swerved to avoid the palm of another barefoot beggar, a boy in tattered shorts. Something told me they'd had more to eat more than I had.

I waved my arm and yelled, "CELLO," one of the few Hindi words I'd managed to pick up during my four years in India. "GO! GET AWAY!"

At the end of the block I turned left to head back to the hotel, which had rusty streaks and the ceiling and jumbo water bugs in its communal shower. The day hadn't seen rain yet, but dark clouds foretell that it soon would. Yesterday's deluge still flooded the streets, and the bottom of my ankle-length skirt had a muddy line that would probably never wash out. How would I survive the next two months of this? All my friends had left for the summer. Nobody would deliberately spend a monsoon season in India if they could help it. Only the losers got stuck in the rain.

"Cleo! Cleo!" I heard someone shout, and I turned to see Birmingham Bobby running toward me. I couldn't believe the scruffy sight of him. Gone was the thick gold jewellery of two years before and his cocky poise. Pimples now polka-dotted his once-smooth skin. "Hello, love," he said, kissing me with enthusiasm and no hint of the former bad feelings between us. "How're you doing? You look great. Got any smack?"

His hopeful grin shrunk as I shook my head and answered, "Only opium."

He grunted. "I'm sick of opium!" As his eyes searched the street for another potential source of free drugs, he related his latest failure in the export business. Then he sighed. "It's not easy here anymore, is it, love?"

"Nothing worked for me this year, either," I told him. "I came to Bombay to keep from starving in Goa. Bila from Dipti's allows me one mango ice cream a day on credit, and Yatin from Spaceways Travel lent me rupees for a few days at the Crown Hotel. I don't know what do when that money runs out."

"Bloody daft how I'm broke," said Bobby, turning around to scan behind him. "Stiffies Hotel threw me out for not paying the bill. I've been sleeping on the street ever since."

Holy cow. I'd heard of down-and-outers who slept on the street with the Indian beggars, but I'd never known one before. Though his was one of the only friendly faces I'd run into, I had an urge to escape him; but before I could utter an excuse, he spotted someone else he knew and dashed off without a goodbye.

To cross an avenue I stepped into a foot of black flood water. Not bothering to raise my stick, I let its already-stained hem float as I waded across. Sleeping on the street with the beggars! Could that happen to me? How far from that was I, anyway? Even with only one ice cream a day, my credit at Dipti's wouldn't last forever, and I'd run out of people who could lend me money. Had he still been a five and able to see me, my nice Jewish father, with his Ritz hotel in Miami Beach, would have med. My nice Jewish mother in New York still thought I was a successful model, though it had been years since I'd sent her a magazine clipping. No, I couldn't let myself fall to that beggar level. Even if it meant leaving India for good.

But I didn't want to leave India. This was my home. Goa was my dream, my fantasy paradise. I couldn't leave it. Everything would be better in the fall, when I could return there—to my house; to Bach, the dog I missed so much; to the nightly beach parties. It was deserted in Goa now—the houses boarded up, the restaurants closed—but as soon as the monsoon ended, my friends would return and it'd be jumping. Goa was my home. I just had to survive the next two months, then I could get back to it.

Having rejected the thought of Rachid for more than a week, I decided Ihad no choice but to involve myself with the slimy Indian. Rachid—yuk. The name "Rancid" would have suited him better.

I detoured to leave messages for Rachid at a juice stand and a shop selling yogurt-type drinks called lassies, and then continued to the hotel. In my room, I avoided brushing the walls and their layer of crud. I didn't sit on the chair, where leatherish filth speckled the upholstery. Touching anything in the room brought shivers to my skin. Before I lay down, I spread a kimono over the bed to hide the sheet's circles of yellow and grey. To endure that place, I'd had to shut a sensor in my brain, the sensor of aesthetics.

On the street the next day, Rachid pulled up beside me in a car crammed with Indian men. Like wolves and coyotes, Rachid and his men travelled in packs.

"Hello, darling," he said. "What can I do for you? Want cocaine?"

I told him I needed to make money. "Don't you have people cashing checks for you or something?" I asked. I'd heard rumours about his underworld businesses.

"For you, darling, I have something better. Something safer."

The job he had in mind did concern checks, traveller’s checks to be specific, and was part of an Operation he ran in several cities. Apparently Rachid had a network of Indians and foreigners working together. In Step One of the scam, his Indians hunted tourists. I would enter in Step Two, where the tourists were conned into parting with their traveller’s checks. Cashing them was the last and riskiest step, and Rachid had a separate group of foreigners for that.

My sensor for compassion must have been numbed also; didn't care what the job entailed.

"Darling, you go back to the hotel and wait," he told me. "We will call you when we're ready. Someone will go with you until you learn the routine. Here is a hundred rupees. Go eat. You need smack? You know you can always come to me, darling. Rachid will take care of you."

I wasn't at the hotel long before I received the phone call. I'd picked up a feast of food, and the call came after I'd wolfed down a pepper steak and was gobbling the third raspberry doughnut. I wasn't sure how the scam worked. I did know I was to play the role of a tourist, removed the diamond from my nose and put on my "government dress," the one I wore to renew my visa. Another crowded car pulled up to the hotel, this time without Rachid, and I squeezed in between an Indian and a seedy looking Frenchman who had dirty hair and dandruff.

"We have an American waiting in a cafe," one of the Indians told "This is your husband." He pointed to Dandruff, who managed a droopy-eyed greeting. Rachid probably employed every junky in Bombay. The Indian continued, "You are to pretend you made money with us yesterday and are back today to make more. Here, take these traveller’s checks. Do not worry. It is easy."

At that moment, my stomach was so nice and full I couldn't have felt other than blissfully content. And one more raspberry doughnut awaited my return.

The car left a block from the café as light rain began. When we walked in. Dandruff recognized another one of Rachid's men, who waved us to the table where he sat with a crew-cut American.

"Hello, hello," the Indian welcomed us warmly. Then, turning to the tourist, he said, "Here is the couple I told you about. Yesterday they earned, what was it, almost two hundred dollars, right?" He looked at us. We nodded. "You had no problems, did you?"

"No," replied Dandruff, my dirty, droopy husband. "Piece of cake."

We drank tea, and then Rachid's man purposely stepped away a minute so the tourist could confer with us and be reassured. "What does he w

ant us to do exactly?" the American asked me. "Buy traveller’s checks for him? That's it?"

"That's all," Dandruff informed him. "He gives us American dollars and we buy him checks. There's a rule that Indian nationals aren't allowed to have foreign currency. But they need traveller’s checks in foreign currency to leave the country. Typical bureaucratic bullshit. We make a percentage of the amount we change."

When we left the restaurant, the four of us took a taxi to a less commercial part of town. The squat buildings looked like factories, and fewer people walked the streets. By this time it was pouring, and Dandruff, the tourist, and I huddled under the tourist's umbrella. Rachid's man, standing in the rain, explained we were to wait there while he went to get the money. Meanwhile, since he would be trusting us with his cash dollars, we were to let him hold our traveller’s checks. The amount of cash we'd be given would match the amount of our traveller’s checks he'd be holding.

"The money is in a safe around the corner," he said, hunching forward to keep the rain out of his eyes. "You give me your checks now and I will put them in the safe and come back with the money."

Following Dandruff's lead, I handed him the traveller’s checks I'd been given in the car. After watching us give the man our Checks, the tourist didn't hesitate more than a second before handing over his.

Uh-oh. I suddenly realized we'd be left waiting there with the neat American until he figured out he'd been ripped off.

"Are you sure this is okay?" he asked as we watched the (Irene had Indian walk away with his two thousand dollars worth of American Express. The rain formed a blur around us. Dandruff left the refuge of the umbrella to sit on a concrete wall. Oh, terrific—now I was alone with the guy. I tried concentrating on my furry Bach back in Goa. Had Bach run away from the Person I'd left him with? Was somebody feeding him? Did he miss me?

"Where are you from?" I asked our victim. Water cascaded off the umbrella, over my elbow, down my leg, and into my left shoe.

"Wisconsin. Ever been there?" Water poured down his back and ruined the crease in his trousers.

I shook my head. My shoe squished as I shifted my weight. I wondered how long this would take.

"We certainly picked the wrong time of year to vacation in India, didn't we?" he stated.

"Um . . . really! My travel agent didn't say anything about a rainy season. Did yours?"

"This isn't a considerate place to have us wait," he commented next. "Is this where you waited yesterday?"

I looked at Dandruff on the wall, eyes closed, letting the rain flow over him. I nodded and tried to recall the taste of the raspberry doughnut. "What do you do in Wisconsin?" I asked, wishing the guy wasn't so dose. I could feel the heat of his hand next to mine as we held the umbrella.

"I manufacture nuts and bolts in specialized sizes. What do you do?"

"Oh, um . . . uh . . . this and that. You know." I'd have to think up better answers.

Fifteen minutes later, our victim started to worry. "Where is that man? He's Tate. Did it take this long yesterday?"

Again I looked at Dandruff. His eyes were still closed. "No, yesterday he came right back. I hope nothing went wrong."

After another twenty minutes our victim groaned. "He's not coming back," he said. "I think we've been robbed."

At this point, Dandruff joined us and wrinkled his forehead in an effort to look concerned. "No! You think so?"

"What can he do with our traveller’s checks?" I asked. "You need identification to cash them."

"The bastard!" exclaimed Dandruff forcefully.

"What do we do now?"

"We must report to the police."

"But we can't tell the truth," Dandruff said with feigned dismay. "What we planned to do is illegal. It will be us who'll be in trouble. We'll have to say the Checks were lost."

"You're right. Or that they were stolen from the hotel room," I added.

Finally, when the tourist surrendered all hope, we agreed to leave separately to report the lost checks.

Later, Dandruff and I split three hundred dollars, our fifteen percent of the man's checks. If the foreigners who cashed them received the same percentage, that still left Rachid a juicy profit; and who knew how many others like us Rachid had working for him.

"Listen," I said to Dandruff, "do you think I can ask them not to leave me in the rain next time? There must be a place with a doorway or an awning or something."

"Don't do that. The more comfortable it is, the longer you'll have to wait. Believe me, it goes fastest when you're out and exposed in a torrential downpour."

After devouring the remaining doughnut, I moved to a room that had its own toilet. What a luxury. Though I wasn't thrilled with my new vocation, the compensations eased my conscience. I went to the Sheraton to buy French bread, Camembert cheese, and a bottle of American shampoo. Oh, boy—I'd be able to wash the sticky soap mess from my hair. I just might survive until September after all.

After four more days with Dandruff, I worked alone.

But I hated it. I hated standing there as the tourists realized their checks weren't coming back. The long wait while hope faded was torture. As they agonized over what the loss meant, I agonized over being the one who caused it.

"I've been saving for this trip for years," said a German woman during our second half-hour of waiting. "I always wanted to visit the Ganges River." She paused to look mournfully in the direction she'd let someone walk away with her traveller’s checks.

I felt awful for her, knowing myself the ordeal of reporting lost checks. If she came to India for only a two-week excursion, she'd probably never dipher toes in the Ganges now. I tried not to think of it. I resisted the image of me as a cretin. I thought of Goa instead. And Bach. And the food I could now afford.

Though I could tell that speculation about my role flickered through people's minds while we waited, nobody accused me outright. What worried me was the possibility of running into somebody at a later date. The tourist area of Bombay was small, and I knew our victims would learn the details of the scam as soon as they returned to their hotels. Undoubtedly their desk clerks had heard of it. It was notorious at American Express, which had even posted fliers with descriptions of Rachid's people. This was big business, and I, for one, received the call at least once a day.

After a few weeks, anxiety that I might be spotted grew to fear and then terror. Visions of being dragged through the street, kicked and cursed at, haunted me whenever I went out. So I bought a black wig and a pair of sunglasses. Now, on top of everything, I felt ridiculous as I slinked down alleys in disguise. If I glimpsed a Westerner on the street, I'd turn to a store window to see if I could recognize the person in the glass reflection before he or she recognized me.

When Rachid suggested I go to Delhi, I was enormous relieved. "Darling, you will like it better in Delhi," he said. "All my people stay in one hotel. It will be like a party. See how I try to make you happy, darling?"

Dandruff came, too. Apparently tourism was booming in Delhi. The three of us flew together, and Rachid took us personally to the hotel. As we entered, the Indian employees steeped their hands and lowered their heads respectfully to him. He must have owned the place. Upstairs, Dandruff and I were introduced to six Westerners, all male, all droop looking, and all sleazy.

A porter showed me to a room. I was impressed: it had its own bedroom.

"Here you are, darling. Is this not cosy?"

During the day, we sat around a central area waiting to be called. The hotel manager would summon us.

"Your turn." The Indian signalled Dandruff.

"What, again? I already went twice today."

"Cleo, you're next."

"But Tin in the middle of a Tandoori chicken," I moaned.

Sometimes we were all out at once. Rarely were more than three of us there at one time. In Delhi I relaxed. With the hotel outside the city centre, I no longer feared running into a victim after the feet I still hated the job, but I was surviving the monsoon. An

d there was a wonderful Bengali restaurant down the block Food! Soon soon I would be back in Goa.

One evening Dandruff didn't return. We notified Rachid. Late that night a knock woke me. Half asleep, I didn't think twice about opening the door until two police officers strode into the room.

Oh, shit.

"You are tourist?" asked a little inspector, looking into corners. "Uh . . . yes."

"Please, you show me your passport."

When I did, he sat on the bed to examine it. The other policeman searched the room at first poking into empty drawers and then rummaging through the suitcase where all my clothes tangled into one big knot. "But you are staying in India what eleven months?" the inspector said, trying to figure out my entry dates. "No, you are making one trip to Bangkok and return. What is your occupation?"

"Oh, um . . . uh . . ."

"Is this correct? It is saying that you are born in 1950. You are twenty-one?" He looked closer at me. "No, you are being no more than eighteen." People always mistook me for younger than my age. He compared me to the passport picture.

Just then the other officer came across a set of traveller’s checks hidden in a bikini bottom He brought them to the inspector, and the two of them smiled Humpty Dumpty-style.

"So! These are your checks? This is your name?"

They weren't and it wasn't.

The police took me away.

A canvas-covered jeep waited in front of the hotel, and in the back wrapped to his ears in a blanket sat Dandruff.

"What happened?" I asked, climbing in and sitting beside him.

He waited till the engine blocked his voice from the driver, then answered, "A tourist recognized me from last year. She called the cops. They beat me. Look, they pulled my earring out." He motioned to his bloody lobe. "The pigs ruined my ear."

Was that supposed to justify his informing on me? Obviously he'd led the police to my door. He must not have mentioned anyone else from the hotel just me.

Goa Freaks: My Hippie Years in India

Goa Freaks: My Hippie Years in India